It's all about buffers: zero-copy, mmap and Java NIO

There are use cases where data need to be read from source to a sink without modification. In code this might look quite simple: for example in Java, you may read data from one InputStream chunk by chunk into a small buffer (typically 8KB), and feed them into the OutputStream, or even better, you could create a PipedInputStream, which is basically just a util that maintains that buffer for you. However, if low latency is crucial to your software, this might be quite expensive from the OS perspective and I shall explain.

What happens under the hood

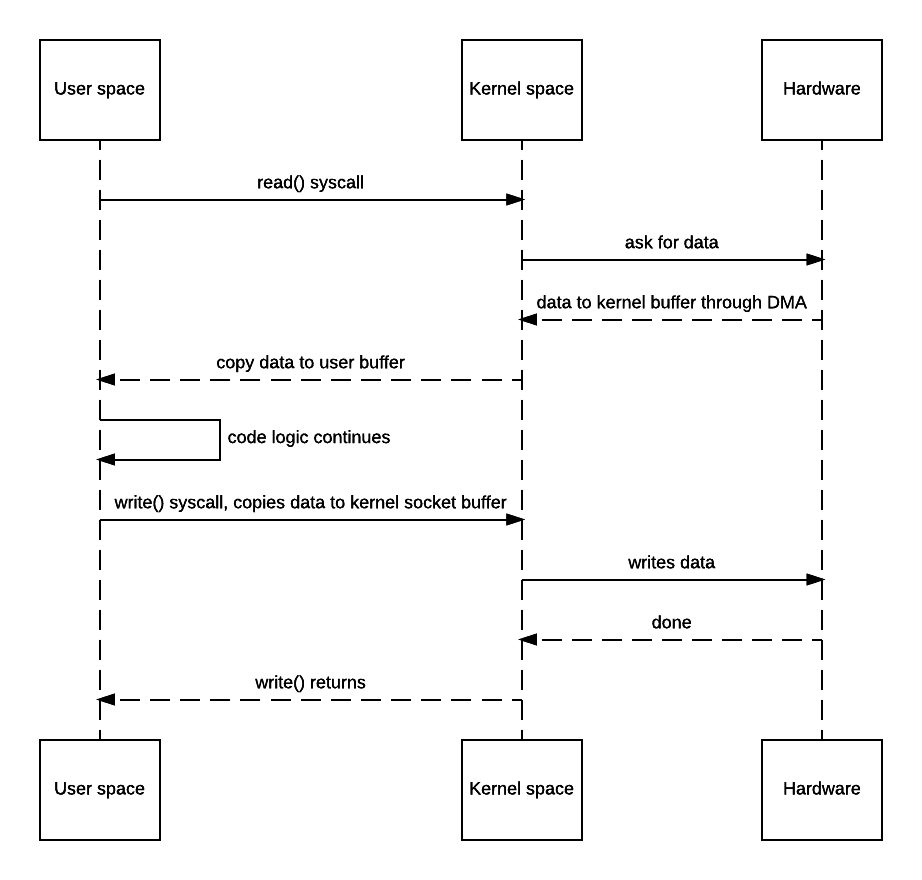

Well, here’s what happens when the above code is used:

- JVM sends read() syscall.

- OS context switches to kernel mode and reads data into the input socket buffer.

- OS kernel then copies data into user buffer, and context switches back to user mode. read() returns.

- JVM processes code logic and sends write() syscall.

- OS context switches to kernel mode and copies data from user buffer to output socket buffer.

- OS returns to user mode and logic in JVM continues.

This would be fine if latency and throughput aren’t your service’s concern or bottleneck, but it would be annoying if you do care, say for a static asset server. There are 4 context switches and 2 unnecessary copies for the above example.

OS-level zero copy for the rescue

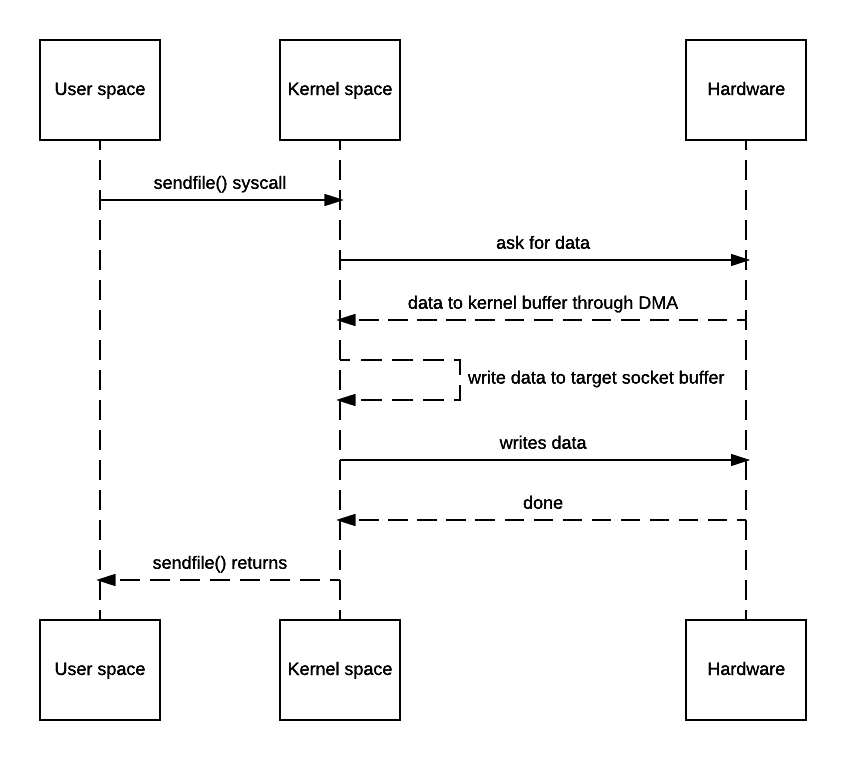

Clearly in this use case, the copy from/to user space memory is totally unnecessary because we didn’t do anything other than dumping data to a different socket. Zero copy can thus be used here to save the 2 extra copies. The actual implementation doesn’t really have a standard and is up to the OS how to achieve that. Typically *nix systems will offer sendfile(). Its man page can be found here. Some say some operating systems have broken versions of that with one of them being OSX link. Honestly with such low-level feature, I wouldn’t trust Apple’s BSD-like system so never tested there.

With that, the diagram would be like this:

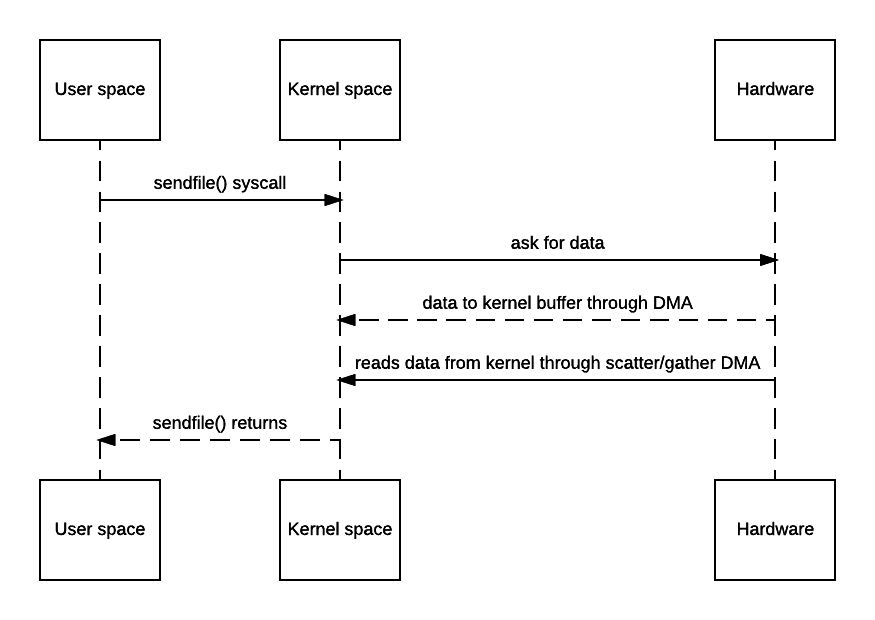

You may say OS still has to make a copy of the data in kernel memory space. Yes but from OS’s perspective this is already zero-copy because there’s no data copied from kernel space to user space. The reason why kernel needs to make a copy is because general hardware DMA access expects consecutive memory space (and hence the buffer). However this is avoidable if the hardware supports scatter-n-gather:

A lot of web servers do support zero-copy such as Tomcat and Apache. For example apache’s related doc can be found here but by default it’s off.

Note: Java’s NIO offers this through transferTo (doc).

mmap

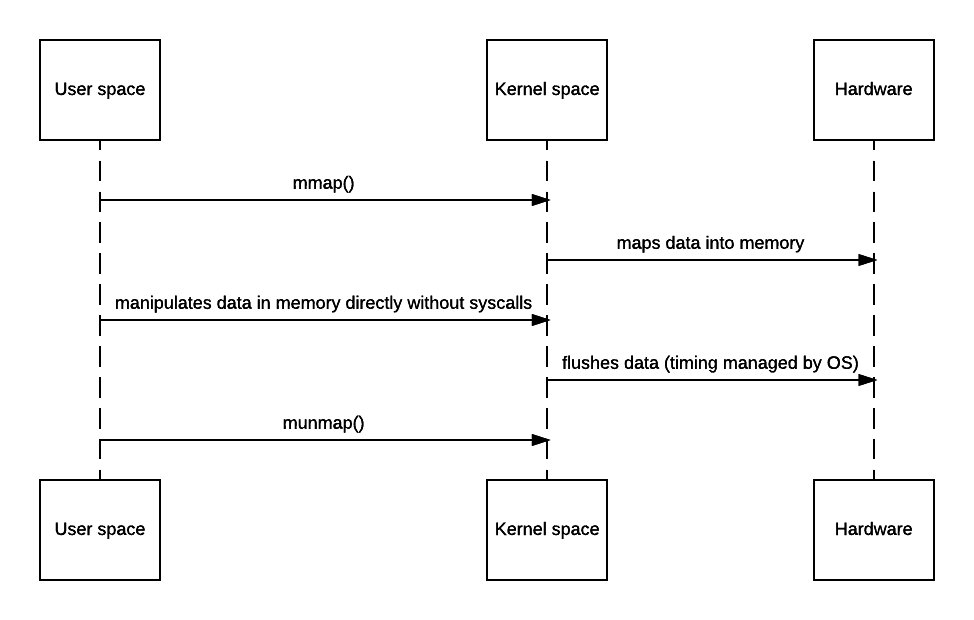

The problem with the above zero-copy approach is that because there’s no user mode actually involved, code cannot do anything other than piping the stream. However, there’s a more expensive yet more useful approach - mmap, short for memory-map.

Mmap allows code to map file to kernel memory and access that directly as if it were in the application user space, thus avoiding the unnecessary copy. As a tradeoff, that will still involve 4 context switches. But since OS maps certain chunk of file into memory, you get all benefits from OS virtual memory management - hot content can be intelligently cached efficiently, and all data are page-aligned thus no buffer copying is needed to write stuff back.

However, nothing comes for free - while mmap does avoid that extra copy, it doesn’t guarantee the code will always be faster - depending on the OS implementation, there may be quite a bit of setup and teardown overhead (since it needs to find the space and maintain it in the TLB and make sure to flush it after unmapping) and page fault gets much more expensive since kernel now needs to read from hardware (like disk) to update the memory space and TLB. Hence, if performance is this critical, benchmark is always needed as abusing mmap() may yield worse performance than simply doing the copy.

The corresponding class in Java is MappedByteBuffer from NIO package. It’s actually a variation of DirectByteBuffer though there’s no direct relationship between classes. The actual usage is out of scope of this post.

NIO DirectByteBuffer

Java NIO introduces ByteBuffer which represents the buffer area used for channels. There are 3 main implementations of ByteBuffer:

HeapByteBufferThis is used when

ByteBuffer.allocate()is called. It’s called heap because it’s maintained in JVM’s heap space and hence you get all benefits like GC support and caching optimization. However, it’s not page aligned, which means if you need to talk to native code through JNI, JVM would have to make a copy to the aligned buffer space.DirectByteBufferUsed when

ByteBuffer.allocateDirect()is called. JVM will allocate memory space outside the heap space usingmalloc(). Because it’s not managed by JVM, your memory space is page-aligned and not subject to GC, which makes it perfect candidate for working with native code (e.g. when writing OpenGL stuff). However, you are then “deteriorated” to C programmer as you’ll have to allocate and deallocate memory yourself to prevent memory leak.MappedByteBufferUsed when

FileChannel.map()is called. Similar toDirectByteBufferthis is also outside of JVM heap. It essentially functions as a wrapper around OS mmap() system call in order for code to directly manipulate mapped physical memory data.

Conclusion

sendfile() and mmap() offer efficient, low-latency low-level solutions to data manipulation across sockets. Again, no code should assume these are silver bullets as real world scenarios may be complex and it might not be worth the effort to switch code to them if this is not the true bottleneck. For software engineering to get the most ROI, in most cases, it’s better to “make it right” and then “make it fast”. Without the guardrails offered by JVM, it’s easy to make software much more vulnerable to crashing (I literally mean crashing, not exceptions) when it comes to complicated logic.

Quick Reference

Efficient data transfer through zero copy - It also covers sendfile() performance comparison.